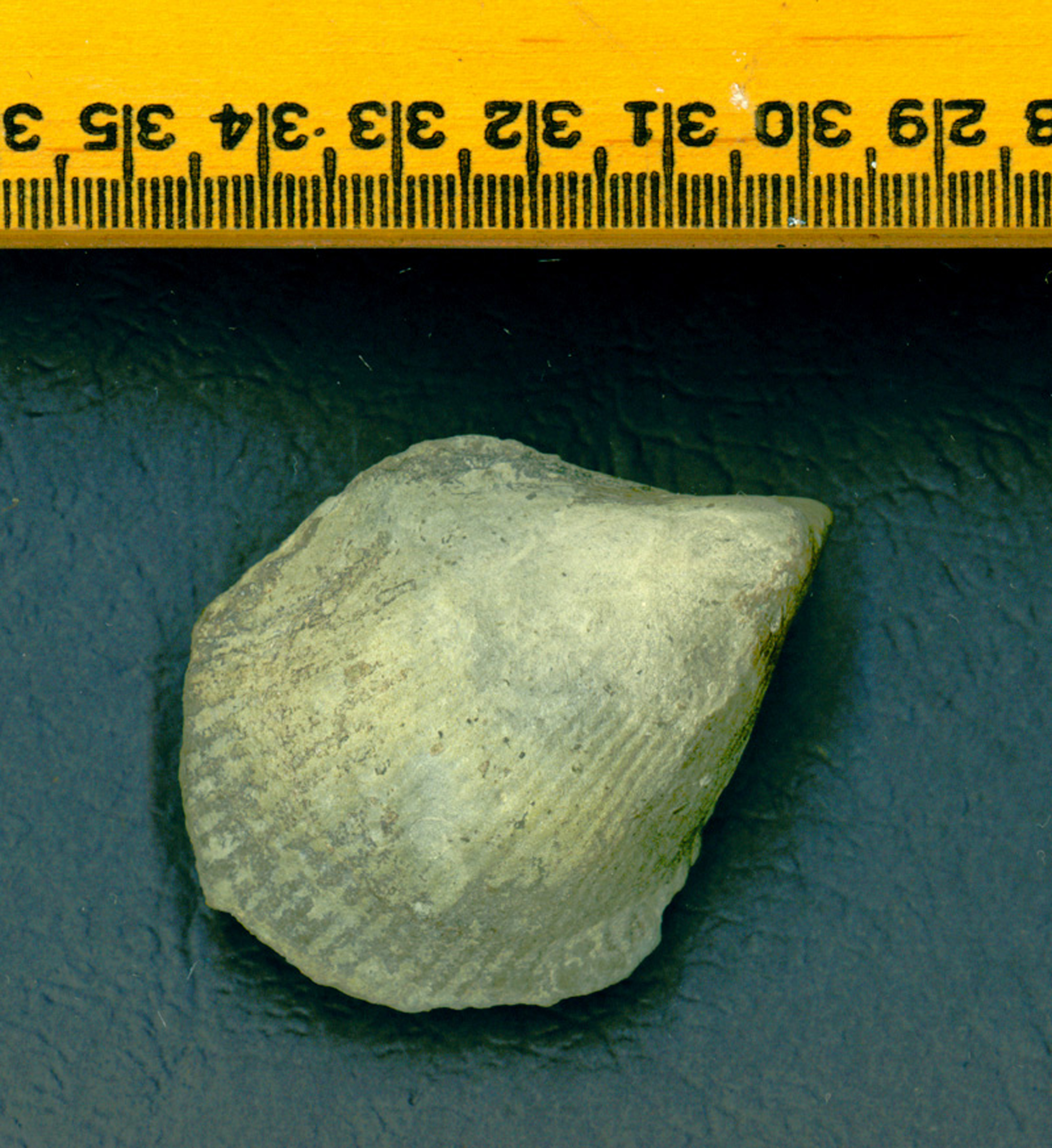

This fossil is the broken-off tip from the bill of a billfish, estimated in age from the Miocene Epoch (23 to 5.3 million-years-ago), possibly belonging to, Xiphiorhynchus, an extinct, giant, double-billed swordfish, or possibly belonging to Tetrapturus pfluegeri, an extant marlin billfish.

I chose these two related species as possible matches to the billfish fossil because both species were abundant during the Miocene Epoch (fossil age) and because the fossil was discovered along the Eastern Atlantic Coast of United States where both species were and are native.

Swordfish Facts

Xiphiorhynchus fossil records show they were one of the first swordfishes to have evolved during the Eocene Epoch (56 million-years-ago), surviving most abundantly through the Miocene Epoch (23 mya) becoming extinct during the Pliocene Epoch (2.6 mya) when one third of the planets megafauna died out due to cooling climate changes.

Xiphiorhynchus was a large swordfish reaching 5 meters (16 feet) long or more, comparable to the Great White Sharks of today. Unlike the “one and only” true living swordfish today, Xiphias gladius (shown below) whose smaller in comparison, averaging about 3 meters (10 feet) long, extinct Xiphiorhynchus had not one, but two equal length swords. During its reign, it would have been a top predator and likely achieved great speed and predatory skills, reminiscent of the many varieties of modern-day billfishes.

Xiphiorhynchus were highly migratory as are modern-day billfishes and would have been spotted along the Eastern Atlantic Coast of America through to the Gulf of Mexico down to Peru and as far south as Antarctica.

Swordfish are named after their long pointed, flat bills resembling a sword.

Marlin Facts

Tetrapturus pfuegeri is an extant species, (still living) from the marlin family, Istiophoridae, of billfishes, which includes about 10 species native to the Atlantic Ocean.

Commonly named, Long Bill Spearfish, it reaches a length of around 2.5 meters (8 feet) with a maximum weight of 58 kilograms (128 lbs). It is quite a fascinating looking marlin fish species.

One of the largest and probably best known marlin is the Atlantic Blue Marlin, Makaira nigricans, which averages 3 meters (10 feet) long and can weigh 825 kg (1800 lbs). The Blue Marlin fossil record dates back from about the middle of the Miocene Epoch around 11 million-years-ago, and also shows they were discovered along the east coast of the United States as well. So the Blue Marlin could be another possible match to this fossil.

Marlins are oceanic species, chiefly found in offshore waters. They are highly migratory and are some of the fastest fish in the sea, reaching 110 km/h (68 mph) in short bursts. A marlin is not a swordfish. The main difference between a marlin and swordfish is that marlins have a more elongated body and a longer, sloping, dorsal fin.

Marlin’s common name is thought to be derived from its resemblance to a sailor’s marlinspike, an iron hand tool that tapers to a point and is used to separate strands of rope.

Marlins are popular sporting fish in tropical seas, consequently, the Atlantic Blue Marlin and the White Marlin are endangered owing to overfishing.

All rights reserved © Fossillady 2025