I Found a Fossil on the Beach and Wondered

You’re enjoying a walk on the beach and something catches your eye lying in the sand. It’s not driftwood or beach glass or even a pretty rock. You suspect you have found something that was once a living creature and you can’t let it go. Has that ever happened to you? A deep sense of wonder and childlike imagination may drive you to find out what you picked up from our freshwater or saltwater sandy-shores. My own sense of wonder led to learn about the fossilized creatures I have found on the beaches of Lake Michigan, including what they looked like when they were alive and how and when they lived. I was also curious to know how they showed up so prevalent along our freshwater beaches. Taking things a step further, I drew illustrations of their living beings included in my article.

- Fossil Facts in the following order:

- Crinoids

- Bryozans

- Brachiopods

- Clams

- Petoskey Stones

- Favosites Honeycomb Corals

- Horn Corals

- Chain Coral Halysites

- Stromatolites

NOTE: The following fossil descriptions are individually included articles in my fossillady site under “Categories” with additional info, illustrations or photos. I decided it would be expedient for Lake Michigan beach fossil-hunters to present them here together in a single article.

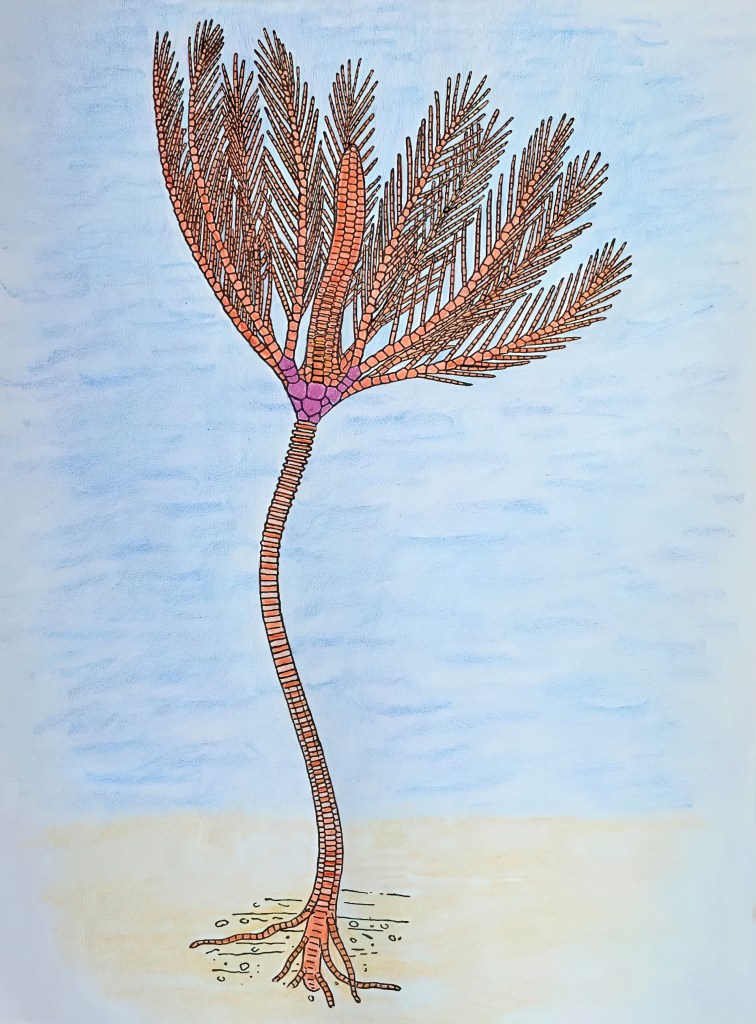

Crinoid Fossils

Crinoid fossils are some of the most common fossils found along Lake Michigan beaches. They’re often referred to as “Indian Beads” because Native Americans are known to have strung together their broken off cheerio-shaped pieces in order to make necklaces. They’ve also been referred to as Lucky Stones because spotting one of the tiny pieces requires a bit of luck! Crinoid animals were sessile creatures—in other words, they remained attached to the sea floor by means of a long single stem. Attached atop of their stem was an intricate cup-like structure from where numerous branching arms grew outwards, much like a plant or tree. The frame works of crinoids were constructed from each individual circular section (shown above) which were stacked one on top of another. The hole in the center of each section contained soft tissue supplying nutrients throughout the animal. Some varieties were known to have towered several meters high off the seafloor. Their entire structure resulted in the living organisms’ beautifully colored and flower-like appearance, which granted them another common name “sea lilies”.

Sea lily crinoids captured tiny food particles passing by in ocean currents with their feathery network of fingers that functioned like traps. Crinoids invertebrate animals fit into the phylum of Echinoderm, meaning spiny skin. They are cousins to starfish, sea urchins, and feather stars.

“Sea lily” crinoids lengthy history dates far back to the Ordovician Period around 500 million years ago, although the fossil record reveals their heyday occurred during the Mississippian Period around 345 mya. Today, there are far few species, but they lack the long meandering stems common in Paleozoic varieties and live in colder, deep ocean depths. For more photos and drawing of crinoids go to another fossillady article specifically about theme HERE.

…

How Are Saltwater Ocean Fossils Found as Far North as Michigan? During their Paleozoic lifetimes, much more of the world’s continents were covered under warm, shallow, saltwater seas, including the Great Lakes regions. When thousands of Paleozoic ocean species died, including crinoids, they became buried in sediment and under certain conditions, fossilized.

Millions of years later, around ten thousand years ago, the giant glaciers sculpted deep basins, forming the Great Lakes. In the process, they also dug into the deep layers of sediment where crinoid remains and their counterparts lay buried and were thusly released. Since then, the perpetual wave action of the big lakes has continued to deposit them on our beaches where we have the privilege of finding them!

Bryozoan Fossils

Bryozoans earn the common name, lace corals, due to their delicately threaded appearance, but they were not true corals. Instead, they were moss-like invertebrate animals. My sample belongs to the family of extinct “Fenestellida” known for their fan-shaped, mesh-like constructs and the genus “Fenestella”. They lived in tight colonies sculpted by hard, limy, branching structures. The colony consisted of thousands of individual animals called “zooids”. Each individual zooid lived inside its own limy tube called a zooecium. The zooecium were the size of sewing needles. A single zooid began the colony. A modern day bryozoan colony has been observed growing from a single zooid to 38,000 in just five months. Each additional zooid is a clone of the very first.

Interesting how bryozoans feed. Each zooid has an opening through which the animal can extend its “lophophore” a ring of tentacles that captured microscopic plankton passing by in the oceanic currents. If one zooid receives food, it nourishes the neighboring zooids joined by strands of protoplasm. If only we humans could be more like them, ensuring everyone on the planet is fed!

Their incredible fossil record dates back 500 million years ago (mya), with 15,000 known species. Today there are approximately 3,500 living species. For more information and photos about bryozoans you can go to the fossillady article specifically about them HERE.

Petoskey Stone Coral Fossils

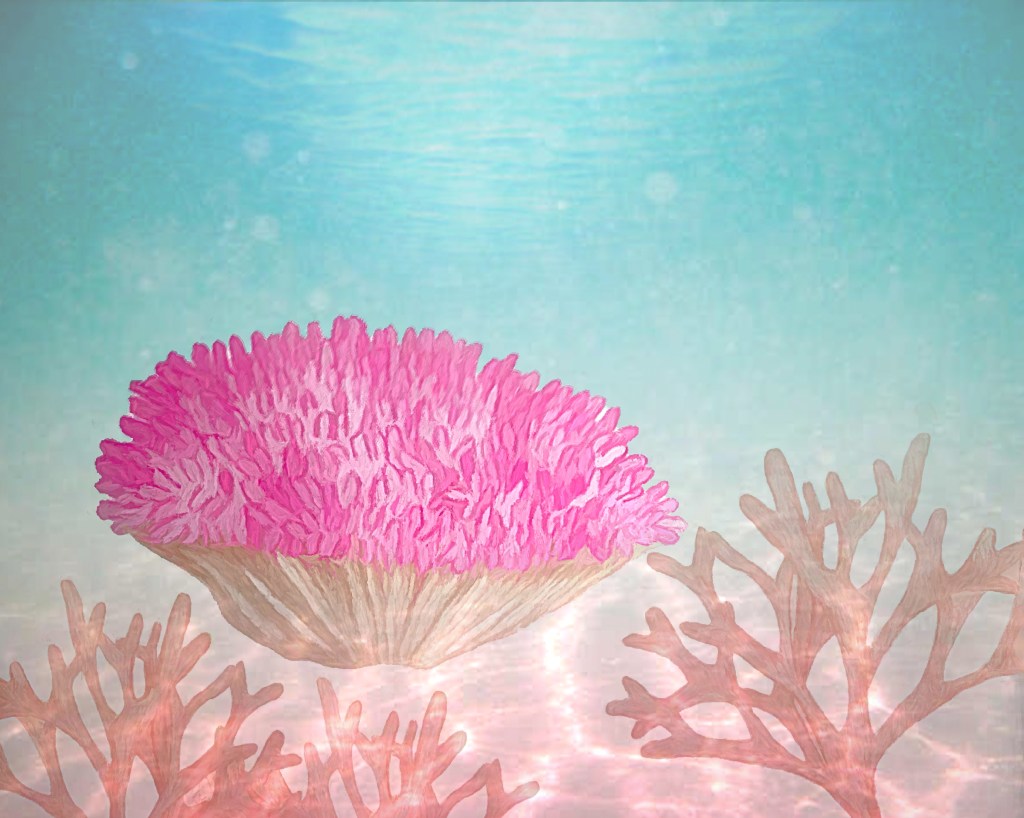

Petoskey Stones “Hexagonaria, percarinata” flourished in mass colonies during the Paleozoic time slot when Michigan and all of the Americas were covered under shallow, saltwater seas. The ancient seascape must have been lit up with a quiltwork of colors created by their vast colonies. Sadly, they became extinct at the end of the Permian Period mass extinction approximately 250 million years ago.

The name “Petoskey” originated from an Ottawa fur-trader chief named, Petosegay. A northern Michigan city was named after him, later, the name was modified to Petoskey. Because the coral fossils are so abundant near the city of Petoskey and surrounding region, Governor George Romney signed a bill in 1965 making the Petoskey Stone the official state stone and fossil.

I found the above Petoskey Stone on Oval Beach in Southwestern Michigan. This sample is rough and raw and unpolished. It’s smoothness and wear is a good example demonstrating Lake Michigan’s natural polishing process produced by perpetual winds, waves, and sand movement. It’s a fairly large sample at least the size of a man’s fist. The sideview of it, shown right, reveals the stem where the coral attached to the ancient seafloor. It’s kind of rare to see this because so many of these coral fossils are sanded down and polished for their intricate beauty and sold as gifts and keepsakes.

Each individual coral hexagon structure called, corrallite, is visible in most Petoskey Stone fossils. Corallites held a single animal (polyp) which opened a mouth to expose tentacles. The tentacles took in food and were also used to sting other organism or even neighboring coral tentacles that came too close. Calcite, silica, and other minerals replaced the original corallite exoskeleton. For addition fossillady photos and information specifically about Petosky Stones click HERE.

Favosites “Honeycomb” Coral Fossils

Favosites fossils are fairly common to find if you live in Northern Michigan, particularly near Charlevoix, but they are more rare to find in Southwestern Michigan where I found the above samples on the beach. Favosites is a genus of corals that belonged to the extinct order of “tabulate” colony corals. Gathered together they created colorful reefs thriving in warm, shallow seas during the same time period as the “Petoskey Stone” extinct corals, which I described above. The favosites can easily be identified by the honeycomb patterns enfolding their exterior fossil remains. These where the casings supporting their individual living coral polyps that could retract inside or stretch out, as with all coral species. Consequently, they are often referred to as, “Honeycomb Corals”, but they are also called “Charlevoix Stones” due to their dominant appearance in that region of Michigan.

The tabulae (horizontal internal layers) of favosites were built outward as the organism grew. These layers can clearly be seen in the fossil photos provided. The walls between each corallite (cup housing for the individual animal polyps) were pierced by pores known as mural pores which allowed a transfer of nutrients between polyps. For more photos and information specifically about favosites in another fossillady article go HERE.

Brachiopod Fossils

No other organisms typify the Age of Invertebrates more than brachiopods. They were the most abundant animals during the Paleozoic Era, except for maybe trilobites. Due to their abundance, paleontologists use them to date rocks and other fossils found in the same rock strata. Countless billions accumulated on the ocean floor with over 30,000 forms. Today there are far fewer species, only around 300, which live mostly in cold, deep ocean environments.

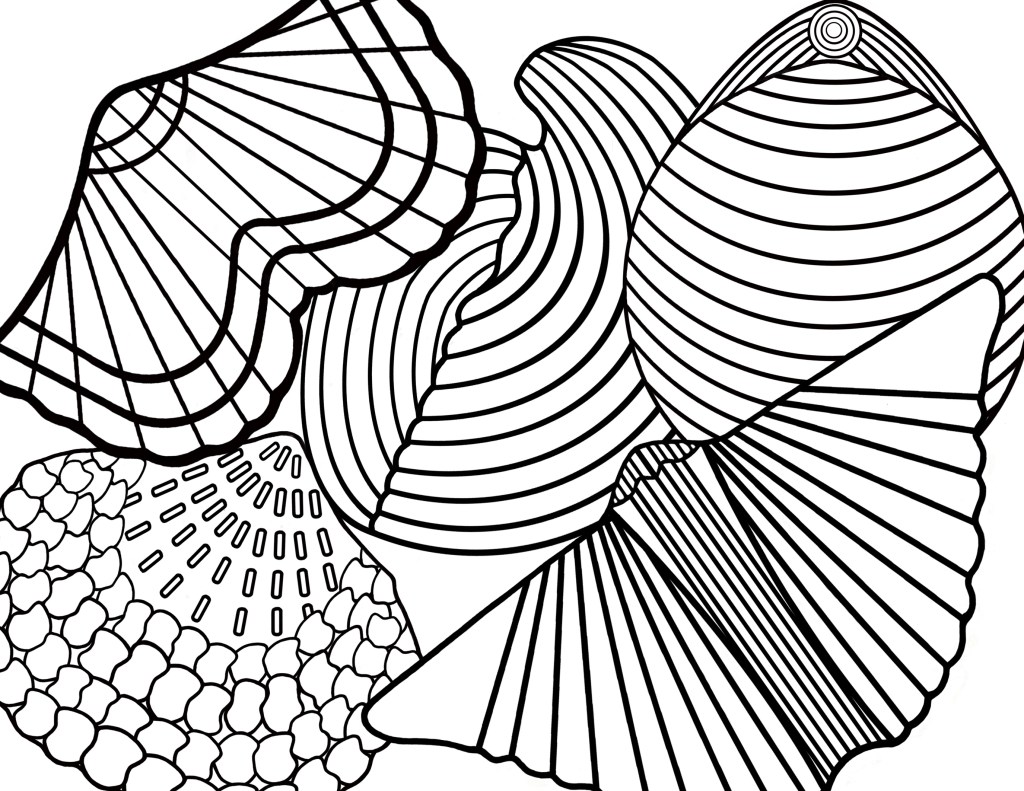

Brachiopods look similar to clams but are very different inside. Also, clams (pelecypods) have uneven-shaped shells, but both top and bottom halves are identical. Brachiopod possess symmetrical shells, left to right, but the bottom shell is smaller. Brachiopods are commonly called “lampshells” due to some species displaying a similar shape as a Roman oil lamp.

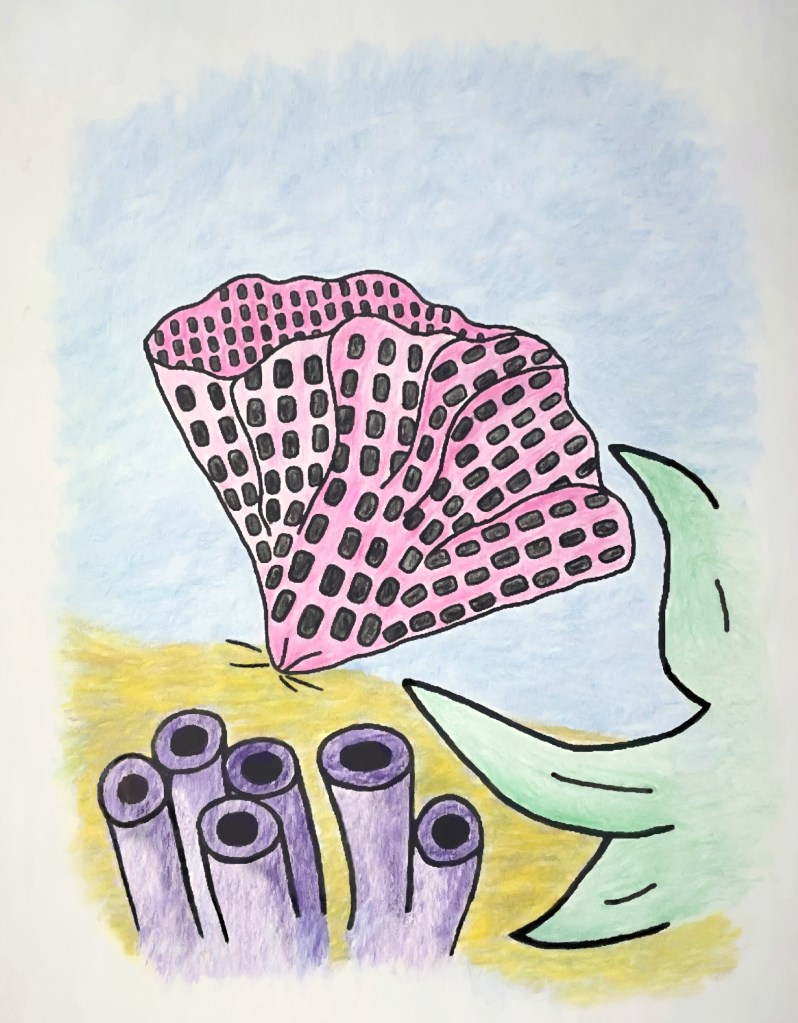

Brachiopods live in communities attached to objects by a muscular foot called a “pedicle”. They strain water in and out of their shells, filtering microorganisms with a crown of feathery tentacles called “lophophores”. They come in a variety of interesting shapes as demonstrated in this image included in my fossil coloring book available for sale! More interesting information about brachiopods by fossillady described HERE!

Clam Shell Fossils

I found these clam fossils on the shore of Oval Beach in Southwestern Michigan. The sample above left clearly reveals hardened muddy sediment that has completely encrusted the clam shell inside and out. The samples above right and below (dark grey) are examples of mold casts of the animal’s shells, where sediment and minerals permeated inside the shell after the animal died. Their smooth surfaces are the telltale demonstration of Lake Michigan’s sand, wind and water movement acting as a polisher.

“Clam” can be a term that covers all bivalves. Some clams bury themselves in sand and breathe by extending a tube to the water’s surface. Bivalve oysters and mussels attach themselves to hard objects, and scallops can free swim by flapping their valves together. All types lack a head and usually have no eyes, although scallops are a notable exception. With the use of two adductor muscles, clams can open and close their shells tightly. Very fittingly, the word “clam” gives rise to the metaphor “to clam up,” meaning to stop speaking or listening.

Bivalves have occupied Earth as early as the Cambrian Period 510 million years ago, but they were particularly abundant during the Devonian Period around 400 million years ago. Their fossils are discovered in all marine ecosystems and most commonly in near shore environments. In 2007, off the coast of Iceland, a clam was discovered that was estimated to be about 507 years old. It was declared the world’s oldest living creature by researchers at Bangor University in North Wales. For more in-depth information about extinct clam species click HERE.

Horn Coral Fossils

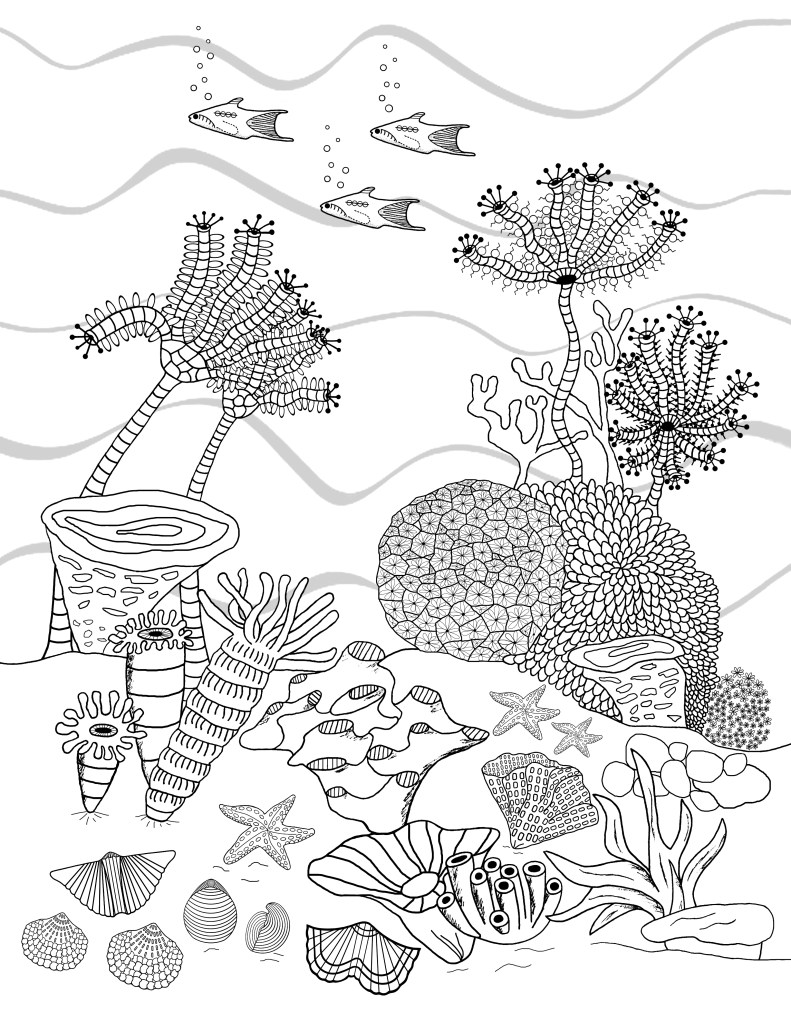

It’s always exciting to find these curious horn coral fossils when combing the beach for something interesting to discover. Horn corals are a genus of corals that belonged to the extinct order of “rugose” corals which appeared as early as 450 million years ago until about 250 mya. That’s an astounding 200 million years living on Earth. Their name derives from their unique horn-shaped chamber with its wrinkled (or rugose) wall. When viewed from its widest opening, it looks like a pinwheel from where the coral polyps once poked out in order to sift microorganisms passing by in the ocean currents. Some species grew two meters high off the seafloor. They were mostly solitary animals, with a few exceptions that grew in mass colonies. For more information and photos about horn corals you can visit another fossillady article specifically about them HERE.

This is a page from my coloring book I illustrated featuring a Paleozoic coral reef vista. It includes horn corals and the other extinct invertebrate animals which I have outlined in this article. See if you can identify them. For purchase of the coloring book or my two fiction books centered on Paleozoic insights that educate as they entertain, you can go to Amazon or IngramSpark.

Chain Coral Fossils

The trail of chains in these beach-smoothed fossil stones is another occasional fun and interesting find from our Michigan beaches. “Chain Coral” is a common name given to the genus “Halysites” coral from the order “Tabulate” colony corals. Halysites survived from the Ordovician Period (starting around 480 mya) through the Silurian Period (ending around 416 mya). As with most coral polyps, they possessed stinging cells, but the polyps were mainly used to grasp plankton floating by in the ocean currents. As their coral polyps continued to multiply, they added more links to the chain, sometimes building large limestone reefs.

Stromatolite Fossils

You’re combing the beach and pick up a common looking smooth stone and admire its sleek texture. You wet the stone and suddenly layers of striations are revealed. That’s what happend with this fossil stone that I found on the beach. It turned out to be a stromatolite fossil and I learned that they are the oldest of all fossils, dating as far back as 3.5 billion years. Their heyday was long before the Cambrian creatures evolved (stromatolites actually paved the way for their existence). Stromatolites were simple cyanobacteria capable of photosynthesis. Their structures grew solid, layered, and varied, some of which looked like giant mushrooms reaching eight feet tall. Through photosynthesis, they changed Earth’s atmosphere from carbon-dioxide-rich to oxygen-rich. Before 1956, scientists believed they were extinct until living stromatolites were discovered in Shark Bay of Australia. Since then, there have been many more stromatolite discoveries around the globe. For more photos and information about stromatolites you can go to this fossillady article specifically about them HERE.

For purchase of the coloring book illustrated by myself or my two fiction books featuring Paleozoic insights that educate as they entertain geared toward middle grade kids to adults, you can go to Amazon or IngramSpark.

All rights reserved © Fossillady 2026