I Found a Rock on the Beach and Wondered

A favorite pastime for beachgoers of the Great Lake states is combing the beaches for interesting treasures. Beachcombing can be a very settling and spiritual experience. I have enjoyed collecting many kinds of treasures along the shores of Lake Michigan, but in particular, beach stones. Follow along to learn interesting facts and identifcation of the assorted types of beach stones, both rare and common!

- Listing of Beach Stones and Beach Boulders found on Lake Michigan sandy shores:

- Basalt (5 types)

- Gabbro

- Septarian

- Limestone (4 types)

- Granite (2 types)

- Diorite

- Gneiss

- Schist

- Sandstone

- Jacobsville Redstone

- Siltstone

- Mudstone

- Claystone

- Chalcedony

- Agate

In case you have a specific rock you were looking for not listed here, you can try my other article on Lake Michigan beach stones HERE which includes in order Syenite, Rhyolite, Pumice, Dolomite, Milky Quartz, Presque Isle Serpentine, Quartzite, Unakite, Diabase, Pegmatite, Conglomerate, Banded Metamorphic Rocks, Quartz Veining, and for fun, Wishing and Heart Stones.

Note: Beach stones and rocks are smoothed and rounded as a result of the wind and waves pushing the stones against the sand, acting as a polisher. The degree of smoothness is also an indication of how far a stone has traveled from the site of its original formation. The smooth rocks feel so wonderfully warm and healing to the touch!

Basalt

Rocks are made up of minerals, and minerals are made up of elements. You can easily look up which minerals make-up any type of rock including basalt described further below in this article. Basalt is volcanic rock, the original rock of Earth’s crust. It covers more of Earth’s surface than any other rock. It is formed from ancient molten rock that cooled quickly when it reached the surface (called “extrusive type”). This is the reason for its fine-grain and heavy-density before gas bubbles, crystallization, or foreign materials infiltrate the rock. Basalt is typically grey to dark grey, but can rapidly weather to brown or rust-red due to oxidation of its iron rich minerals and can further exhibit a wide range of shading due to regional geochemical processes.

Most extrusive igneous rocks in Michigan were formed from ancient, quiet, lava flows which reached the surface through long cracks and crevices in the Earth’s crust; also, from remnants of mountain peaks that have withered away. Just imagine, when you find a basalt rock on the beach, you’re likely holding in your hand at least a billion-year-old chunk of Earth. Below is a brief description of four special types of basalt; Ophitic, Vesicular, Amygdaloidal and Porphyry.

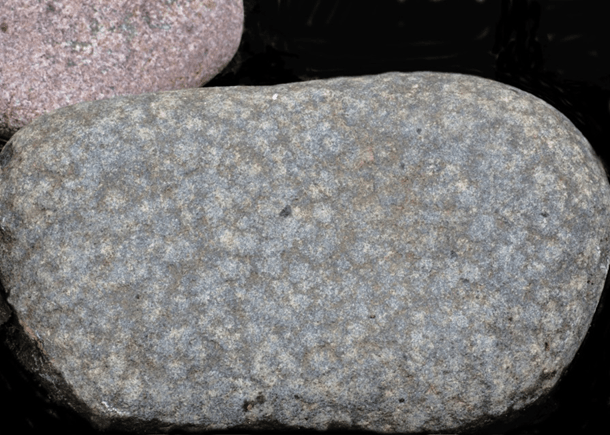

Ophitic Basalt

Ophitic Basalt looks like a basalt rock that has been decorated with light-colored snowflakes. The snowflakes are formed from tiny feldspar crystals within the basalt lava. Because the feldspar crystals eroded at different rates than the basalt base, there is often a slightly mottled texture to these stones. The sample above was a small boulder found on the beach and was quite heavy to carry in my arms!

Vesicular Basalt

Occasionally, we find these most-curious pitted stones on the beaches. After some research, I finally understand how they got that way. They are called “vesicular basalt,” which means basalt with textures, and if the deep pits (vesicles) cover more than half the surface of the rock, it’s called scoria. What causes the vesicles or pits in the rock? The basalt-making molten rock cools down quickly before gas bubbles from deep inside Earth’s surface have the chance to make their way out. When the lava reaches the atmosphere, the bubbles inside can blow out, leaving spherical-pitted impressions.

Amygdaloidal Basalt

This is what can happen, yet later; the vesicles (holes) can fill in with other minerals and the fillings are called amygdules. The basalt is then referred to as amygdaloidal basalt. If the lava flow is in motion when the blowholes are being formed, the holes may be drawn out and elongated, as you can see in the sample above.

Basalt Porphyry

What is porphyry? In various rock types (in this case, basalt), when you see large crystals of a mineral embedded within other finely ground minerals making up the mass, it’s porphyry or porphyritic rock. (You can tell the porphyry basalt apart from the above amygdaloidal basalt sample by the absence of empty pits). The porphyry beach stones are more rare to find. This sample of basalt has a greenish cast likely due to the inclusion of the mineral olivine; and calcite is likely the mineral speckled within the basalt mass.

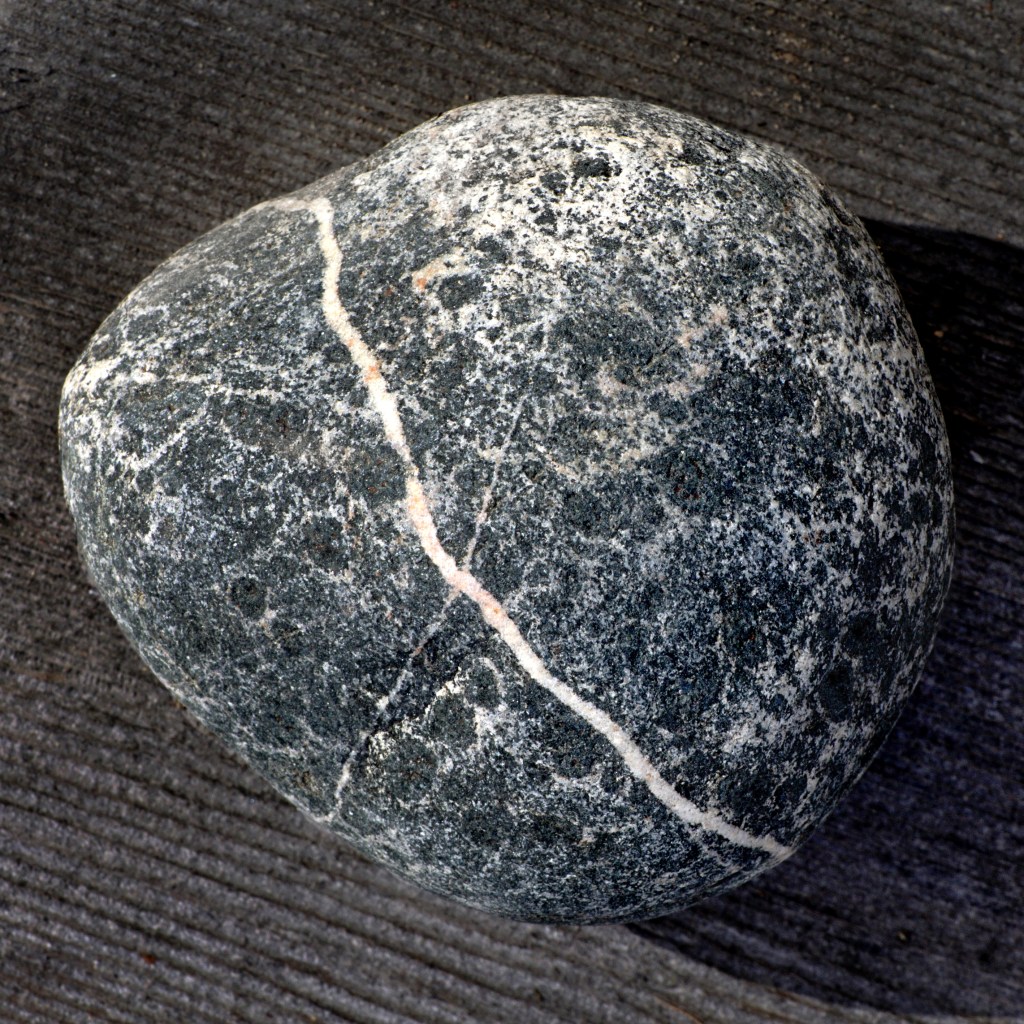

Gabbro

Gabbro is igneous rock which cools slowly (intrusive) deep below the Earth’s surface causing its minerals to crystallize. It’s sometimes called “black granite” for its similar, coarse-grain appearance to granite, but a large proportion of its iron-bearing minerals make gabbro heavier and usually darker in color. Gabbro can also be gray and dark green. You may observe fewer light-colored mineral grains. Unlike many other igneous rocks, gabbro usually contains very little quartz, although the sample I collected has a quartz vein running all the way around it.

Gabbro has the same mineral composition as basalt (olivine and pyroxene silica minerals, with smaller amounts of plagioclase feldspar minerals and mica). But whether basalt or gabbro forms, depends upon the cooling rate of the magma, not its composition. While gabbro is coarse-grained, which cools slowly during the molten stage (intrusive), basalt is fine grained that cools quickly (extrusive).

Septarian Brown Stones

Interesting how they formed; around 50 million years ago, iron-rich mud and clay formed over a shallow ocean floor that covered much of Michigan and other territories of the USA. At some point, the water receded drying out the muddy substrate giving way to cracks and fissures. Later, calcite infiltrated the open veins via ground water and gradually filled them in. Then some time after that, pieces broke apart most likely caused by the ice glaciers that scraped and ripped the bedrock. Geologist now identify the rock pieces as Septarian Stones or Septarian Brown Stones.

Septarians are found only in certain areas of Southwestern Michigan and very few other places around the world. Locals call them “lightning stones” or “turtle stones” for the resemblance. The photos below are good examples of the cracking process. Sometimes the stones break completely apart and we find thousands of smoothed, broken-off sections on the beach.

Limestone

Limestone is a sedimentary rock composed mainly of the skeletal fragments of marine organisms such as corals, clams, or mollusks. Its major mineral contents are calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of the compound calcium carbonate. Marine animals grow their shells by extracting calcium carbonate from the water, which is quite fascinating when you think about it! There are several types of limestone lying on the beaches of the Great Lakes. Below is a descripton of four types; Compact, Crinoidal, Fossiliferous and Tuffa Limestone!

Compact Limestone

Compact limestone is composed primarily of tightly packed calcium carbonate derived from the remains of marine organisms. It can vary in color from white, yellowish, pinkish, red, gray, or even black, depending on the presence of other minerals. It has a very fine texture and is denser than other types of limestone. The first sample shown above is a large piece with rounded edges and has been flattened, hence the name “shingle” for flat stones found on beaches.

Crinoidal Limestone

Crinoidal limestone contains a significant amount of crinoid fossils. Crinoids are extinct invertebrate organisms with limbs that branched out from atop a long narrow stem. They lived as far back as 500 million years ago. They fed by sifting or filtering microorganisms from the ocean water with tentacle like feelers (see drawing). With keen eyes, we sometimes find broken stems from the fossilized remains of these marine creatures or we find individual cheerio-shaped pieces broken off from the stems visibly embedded in the rock samples above and below.

Fossiliferous Limestone

Fossiliferous limestone (shown above) are found fairly commonly in certain pockets on the beaches of Southwest Michigan. Fossiliferous limestone contains a visible abundance of broken fossil pieces such as the shells of mollusks, clams, crinoids, and other invertebrate organisms. Like other limestone, fossiliferous limestone is composed of the mineral calcite. It can be white, pink, red, reddish brown, gray, and even black, depending on the mineral makeup. We find many reddish-brown colored samples on our beaches due to the infusion of iron.

Tuffa Limestone

Tuffa Limestone is a porous limestone that forms from the precipitation of calcium carbonate, often at a hot spring or along the shoreline of a lake where waters are saturated with the chemical compound.

Granite

It’s thrilling to find these round, bird-egg-shaped granite stones on the beach. With their varied colors and patterns, they create beautiful works of art. Granite is another type of rock we find quite often on our Great Lake beaches in the form of pebbles, cobblestones, and boulders.

Granite makes up 70–80% of the Earth’s crust. It’s an igneous rock that cools slowly during its formation deep within the Earth. The slow cooling (intrustive type) allows for the process of crystallization of molten rock. The crystallized, coarse-grained minerals can easily be seen with the naked eye in each rock. Colors vary from red, pink, gray, to white with black grains, depending on the amount and mix of minerals.

What gives granite its color?

- Quartz – typically milky white in color

- Plagioclase Feldspar – typically off white

- Alkali or Potassium Feldspar – typically salmon pink

- Biotite Mica – typically black or dark brown

- Muscovite Mica – typically metallic gold or yellow

- Amphibole Hornblende – typically black or dark green

Special Granite – Above, are two samples demonstrating the variances in granite’s colors depending on mineral content. Can you guess their mineral content based on their color?

Although granite underlies much of the Earth’s surface, it doesn’t often rise up to where we can find it. The Canadian Shield is an enormous granite formation covering most of the country. It is the nearest place to Michigan where granite is found above the crust. So how did it find its way to Michigan’s shores? If you guest the glaciers from past ice ages, you would be right. The granite stones were scraped and carried south from Canada.

Porphyritic Granite

Porphyry or porphyritic rock is made up of a finer-grained rock mass containing larger crystals, in the case of granite, feldspar crystals. Porphyry rock is typically made up of a basalt base but sometimes it can be made up of a granite base with larger, jagged, rectangular crystals within. The larger crystals in the sample shown above have been smoothed by the wave and sand action of the shoreline. Porphyritic crystals are generally white, pink, or orange.

Granite is more difficult to identify as porphyritc form because of its already-coarse grain, but look for stubby, square, or hexagonal crystals that are larger than the other grains within the granite rock. You can clearly see this in the samples I have provided above found on a Lake Michigan beach. Here’s how it happens: As the feldspar minerals in granite begins to crystallize, the process is disturbed when the molten rock is quickly erupted, freezing the well-formed feldspar crystals in place while the rest of the rock quickly cools and fills in around the crystals.

Diorite

Diorite is another of several types of coarse-grained igneous stones that can easily be confused with granite. Diorite’s chemical composition is intermediate between gabbro (described above) and granite.

How to tell the difference between diorite, granite, and gabbro? The best way to tell diorite from granite is by the salt-and-pepper appearance of diorite which differs from granite’s combination of various colors. To tell diorite from gabbro, look for gabbro’s darker color. If you have in your hand a granite-looking rock with obvious pink feldspar and more than 20% quartz, you probably have granite, not diorite or gabbro. Also, diorite is composed with an almost-equal mixture of light-colored minerals, such as sodium-rich plagioclase (a certain type of feldspar mineral), to dark-colored minerals such as amphibole, hornblende, or biotite mica.

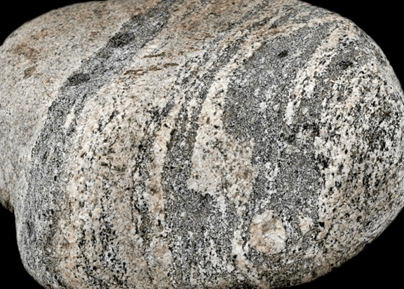

Gneiss

Did you ever wonder how some rocks have bands or stripes? They are some of the most attractive stones, like gneiss for instance, which I only occasionally find on the beach.

Gneiss (pronounced “nice”) usually forms at convergent plate boundaries. It is a high-grade metamorphic rock formed under intense heat and pressure. The original mineral grains recrystallize, enlarge, flatten, and reorganize into parallel bands which make the rock and its minerals more stable. While the chemical composition of the rock may not have changed, its physical structure will look completely different from the original parent rock.

The bands in gneiss are often broken, can be foliated (folded), and can show different widths. Individual bands are usually 1-10 mm in thickness. Layers larger than that imply that partial melting or the introduction of new material probably took place. Such rocks are called “migmatites.” Hence, my boulder sample above would be termed “migmatized gneiss.” It is not well understood how the segregation takes place.

The granular light-colored minerals in gneiss are calcium, sodium, and potassium-rich minerals such as quartz, and also various types of feldspar. The dark-colored layers consist of iron-magnesium-rich minerals including biotite, chlorite, garnet, graphite, or hornblende. The texture is medium to coarse—coarser-grained than schist but, as with the other rock types, the gneiss we find on our beaches has been ground down until it’s somewhat smoother.

What is the difference between gneiss and granite?

- Granite is an igneous rock, whereas gneiss is formed after metamorphosis of granite.

- Most—but not all—gneiss is obtained from granite. There is also diorite gneiss, biotite gneiss, garnet gneiss, and others.

- The mineral composition of granite and gneiss are the same. However, the transformation of granite due to high pressure and temperature leads to the formation of gneiss.

Schist

Schist is a medium-grade metamorphic rock formed by the metamorphosis of mudstone and shale or some type of igneous rock such as slate. As a result of high temperatures and pressures, the coarser mica minerals (biotite, chlorite, muscovite) form larger crystals. These larger crystals reflect light so that schist often has a luster (the photograph doesn’t exhibit the luster, but it’s there). Due to its extreme formation conditions, schist often reveals complex folding patterns with a tendency to exhibit split sheets or plates of mica arranged roughly parallel to each other There are many varieties of schist, and they are named for the dominant mineral comprising the rock, e.g., mica schist, green schist (green because of high chlorite content), garnet schist, and so on. I find these only occasionally on shoreline.

Sand Stone Boulder

Sandstone

Sandstone is a sedimentary rock that forms when small quartz sand grains cement together under high pressure while silica, calcium carbonate (calcite), or quartz precipitates and acts like a glue around the grains. These minerals are deposited in the spaces between the grains of sand by water. Over the course of thousands, even millions of years, the minerals fill up all of the spaces. At a close look, you can see the tiny particles in the rock almost as if you were holding sand in your hand. When you’re at the beach, try examining the sand very closely to discern the tiny quartz crystals and different colors of other minerals contained in it, including feldspars, micas, calcite, and clays.

Depending on the minerals, sandstone can be white, yellow, pink, and almost any color, depending on the impurities within the minerals. For example, red sandstone results from iron oxide in the rock and often causes bands of color. Sandstone rocks form in rivers, deserts, oceans, or lakes. It feels gritty to the touch.

Jacobsville Redstone Sandstone

Jacobsville Sandstone, or Redstone, is generally red due to the presence of highly oxidized iron cement which binds together the grains of quartz. The stone is typically mottled with various pinks, whites, and browns, exhibiting either many streaks or spherical spots caused by leaching and bleaching. It forms a wide belt throughout Northern and Upper Michigan and was quarried rather extensively at one time for use as building material which built the cities of Northern Michigan and elsewhere in the Great Lakes region. As with many stones that formed northward in Michigan, the big lake brings them southward to where I find them in lesser amounts. Estimates for the age of the Jacobsville Formation Range is in the late Mesoproterozoic Era about 1.05 billion years ago until the Middle Cambrian Period.

Siltstone

After some stubborn digging around, I finally believe I understand the difference between sandstone, siltstone, mudstone, claystone, and shale. They all fall under “clastic” sedimentary rocks formed by weathering breakdown of rocks into pebbles, then into sand, then silt, then mud, then clay and last into shale, all from exposure to wind, ice and water. At each step the particles become smaller with shale having the finest grain. All the clastic sedimentary rocks are cemented very much the same way in which sandstone is pressed together described above. Silica, calcite, and iron oxides are the most common cementing minerals for siltstone. These minerals are deposited in the spaces between the silt grains by water. Over the course of thousands or millions of years, the minerals fill up all of the spaces resulting in solid rock.

Silt accumulates in sedimentary basins throughout the world. It occurs where current, wave, or wind energy cause sand and mud to accumulate. Siltstone is very similar in appearance to sandstone, but with a much finer texture. It has a slight grit texture to it and is more difficult to distinguish the mineral particles than sandstone. When handling siltstone, a residue of the same color as the stone can rub off on you hand. Siltstone is usually gray, brown, or reddish brown. It can also be white, yellow, green, red, purple, orange, black, and other colors. The colors are a response to the composition of the grains, the composition of the cement, or stains from subsurface waters.

Left: Mudstone Right: Claystone

Mudstone or Claystone

I described above how mudstones and claystones are clastic sedimentary rocks formed similarly by way of sandstones and siltstones. But I will mention that we especially find the brown mudstones in abaundance on certain beaches in the southwestern regions of Michigan. They are the same type of stone that form the Septarian brown stones. The mudstones and claystones wipe off a residue when handling them due to their fine-grained texture. The last stone in the chain of the sedimentary clastic stones with the finest ground-down grains is shale, but we find very little of it, if at all on the beach. This is likely because shale easily breaks apart at parallel stratifications and due to the extreme ice, wind, and wave action of Lake Michigan, they get demolished.

Chalcedony and Agate

Without being totally certain, I believe these pretty little stones are one type or another of the gemstone chalcedony. They are penny-size and have a smooth, waxy texture. In order to spot these on the beach you need to look very closely along the shoreline where beach gravel is abundant, but I have found quite a few even though they are usually quite small. Michigan’s northern regions and upper peninsula are excellent places for finding chalcedony and other gemstones such as agates.

Top: Agate Bottom: Forms of Chalcedony

Chalcedony and Agate Explained

Rock and minerals can be very complicated but fascinating to study. For a bit of geochemistry about chalcedony and agates, it only makes sense to begin with the microchrystalline quartz, chalcedony. Chalcedony forms where water is rich in dissolved silica and flows through weathering rock. When the solution is highly concentrated, a silica gel can form in the walls of the rock cavities. The gel will slowly crystallize to form microcrystalline quartz (very small crystals of quartz), in other words, chalcedony. Agate and many other microcrystaline quartz are a type of chalcedony all considered gemstones.

Chalcedony can be banded, have plumes (fluffy inclusions), have branching patterns, or have delicately mottled surfaces of leafy green, honey brown, and creamy white. They might also have mossy and other colorful structural patterns within. Chalcedony is often blue but can be almost any color. It’s typically translucent but can be opaque with a milky appearance. It feels very waxy, greasy, or silky to the touch. Agate is generally translucent to semi-transparent and most often is banded. Observing bands in a specimen of chalcedony is a very good clue that you have an agate. However, some agates do not have obvious bands. These are more rare and may show branching-out, mossy inclusions. Typically, an agate is the size of a golf ball and feels heavier than it looks due to its density. It also has a waxy feel to it.

More forms of chalcedony that are possible to find on certain Great Lake beaches, particular Northern Michigan or Wisconsin along the beaches of Lake Superior.

- Aventurine (most often green, speckled, shimmery – opaque)

- Bloodstone (dark green with red speckles – semi-transparent to opaque)

- Carnelian (red to amber, vibrant, mottled patterns to banded – translucent)

- Chrysoprase (apple green, uniform, fewer patterns – translucent to semi-opaque)

- Onyx (solid black or white-banded black – opaque)

- Chert (most often grey, fewer patterns, solid – opaque) Native Americans used to make arrowheads.

- Jasper (most often red with patterns, swirls, bands, or spots – opaque)

- Sard and Sardonyx (reddish-brown banded – transparent to translucent)

- Tiger’s Eye (gold, banded, glistening sheen – semi translucent to opaque)

Final Note: In early spring after the snowmelt, the movement of winter’s ice and snow tends to push and pile rocks further up onto the sandy shores; in some locations by the thousands. Later in the season, the wave action of the big lake washes many of the rocks back into the water and the steady summer winds bury some of them under the sand. Consequently, I find spring to be the best season for rock hunting. But I should mention that some beaches have very few stones, while other pockets are loaded with them.

To end, I leave you with a lovely photo of beach stones settled on a creekbed where it flows into the shoreline of Lake Michigan!