Brief Intro

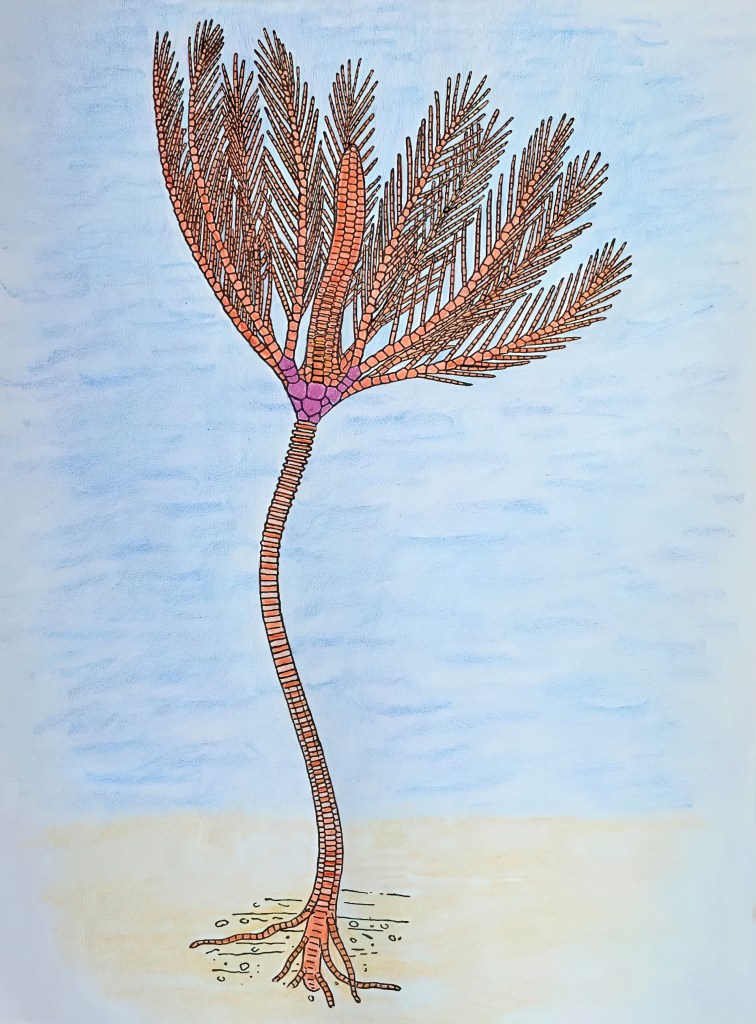

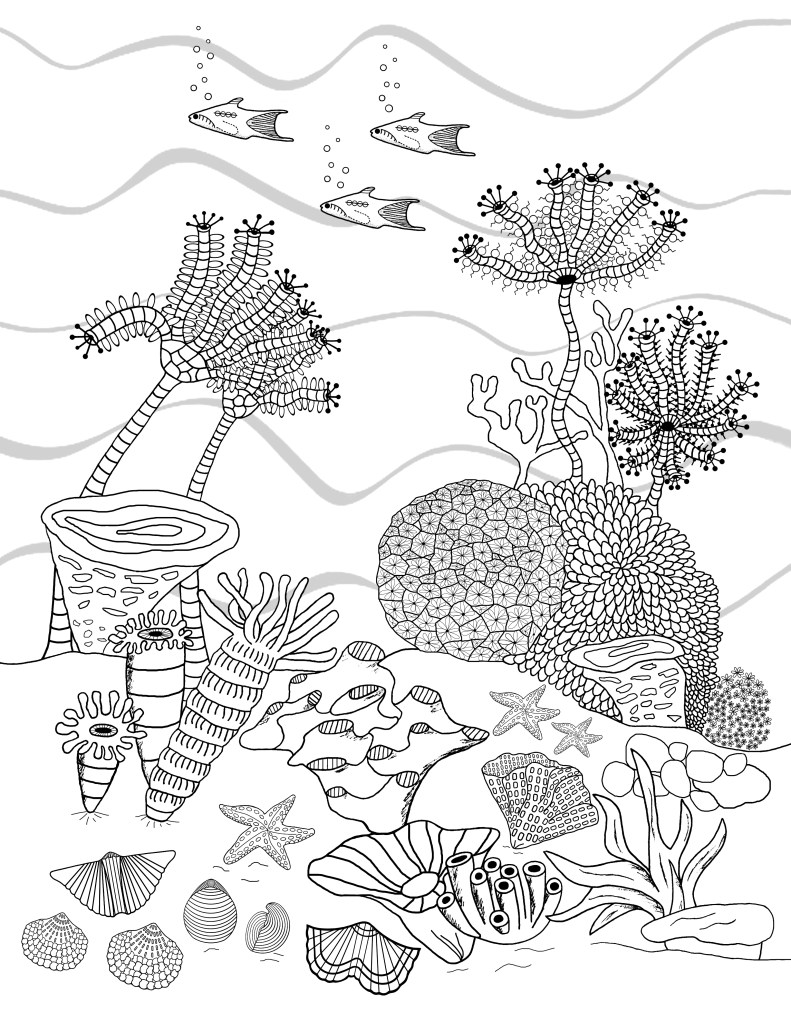

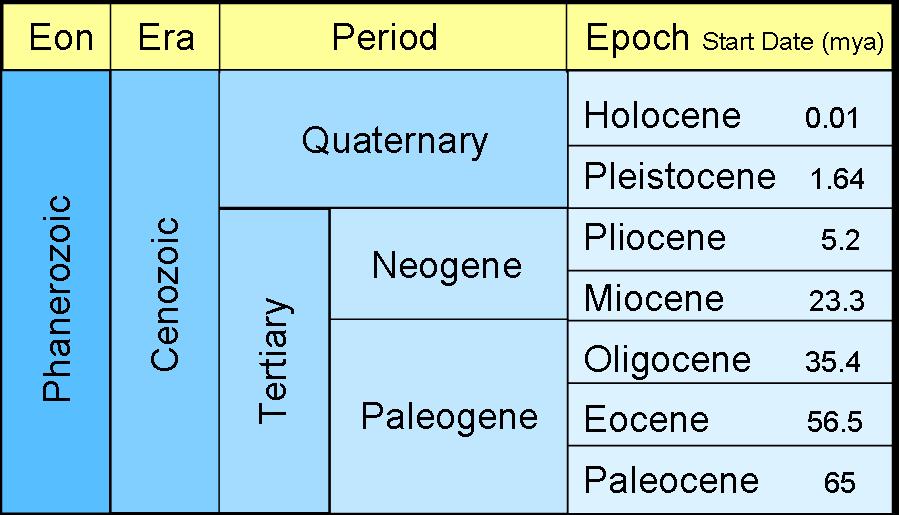

The word “clam” can be used to cover all bivalves, including scallops, oysters, arks, and cockles, to name a few. Did you know that there are more than 15,000 species of clams around the globe? Amazing, right? Clams and other bivalves first appeared in the fossil record as tiny creatures as early as the Cambrian Period over 500 million years ago. Beginning around the Devonian Time Period approximately 400 mya through to the Mesazoic Era, they gradually developed into abundant forms. Follow along to learn interesting facts about clams and to help you identify those clamshells you couldn’t resist picking up from the sandy seashore.

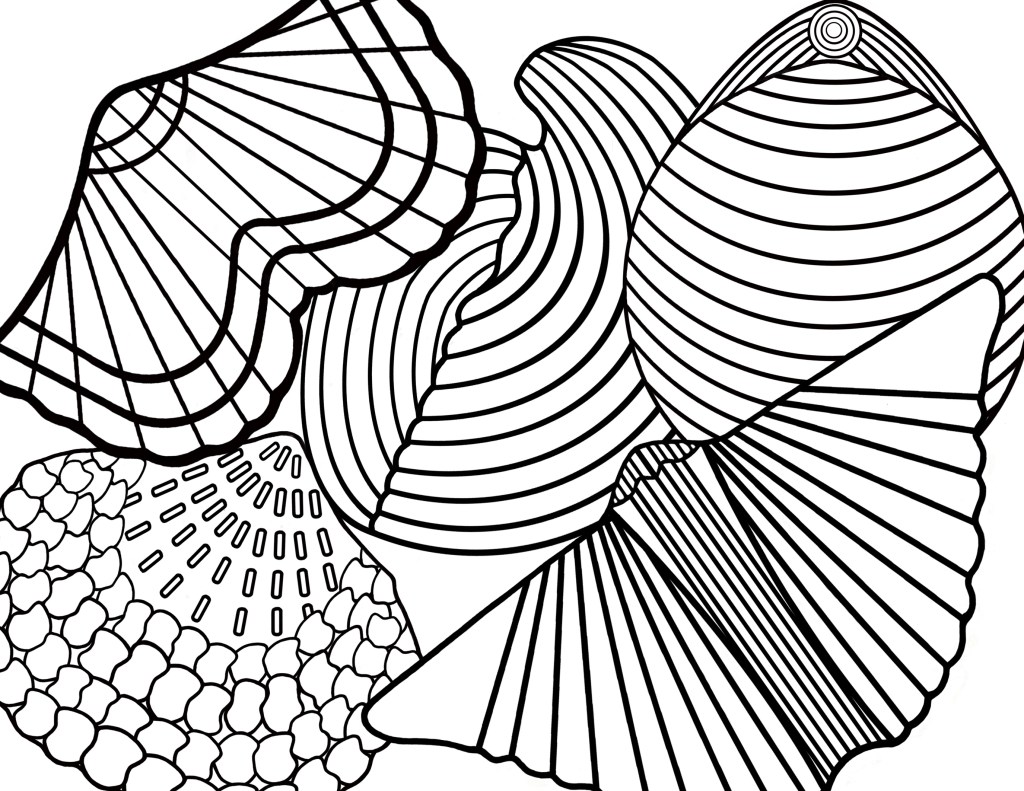

Eleven Clamshell Identifications from my Collection in the following order:

- Coquinas

- Disc Dosinia

- Atlantic Surf

- Eastern Oyster

- Jewel Box Oyster

- Atlantic Thorny Oyster

- Digitate Thorny Oyster

- Jingle Shell Oyster

- Atlantic Kitten Paw

- Tampa Tellin

- Speckled Tellin

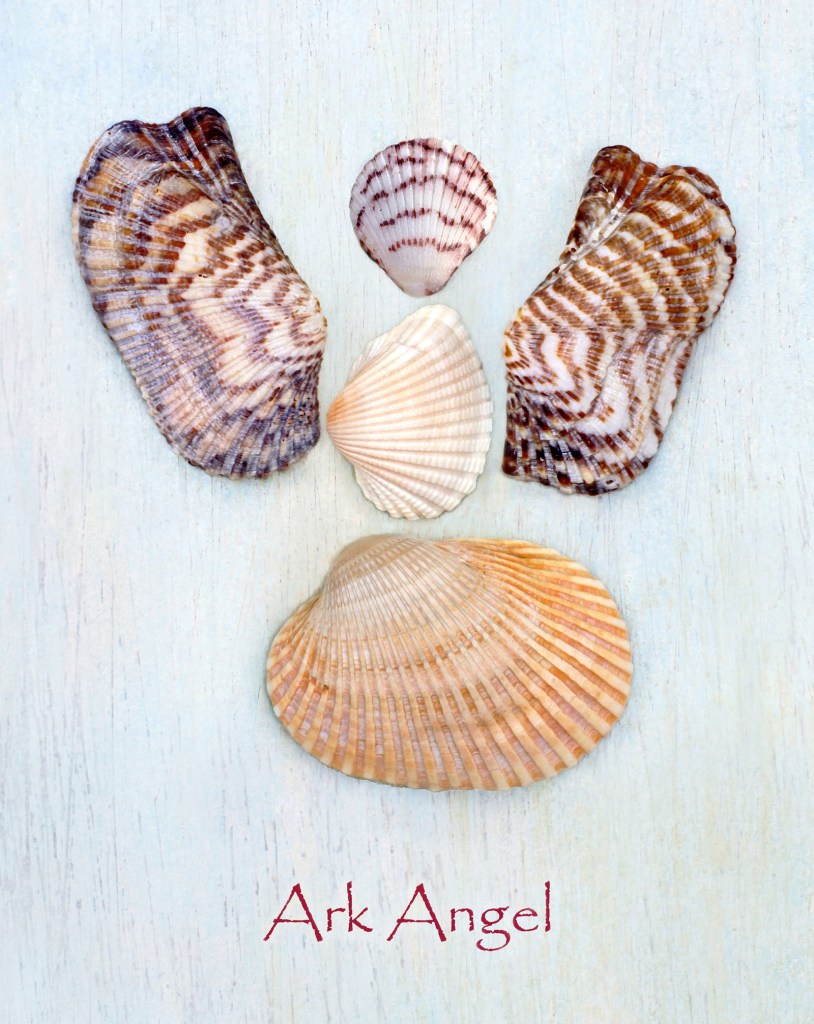

For addional Fossillady clam ID including Arks, Angel Wing, Cardita and Lucines click HERE

1. Coquina Clam

Coquina Clamshells (Donax variabilis) are inspiring with their display of variable colors of the rainbow. The colors can range from yellowish-brown to blue, lavender to green to pink and typically exhibit a plaid pattern. Their shells are asymmetrical from their pointed beak, slightly elongated and inflated. These are little clams that create the activity you see at the tide line of the surf. With the aid of a fleshy foot, they dart about and can bury under the sand in a twinkling. Apparently, they are sensitive to light and rush to get back into darkness under the sand. They are great in soup, and desired in crafting for their beauty.

- Size: Up to 3/4 inches

- Habitat: Sandy shallow subtitle zones

- Range: Virginia to both coasts of Florida and Texas

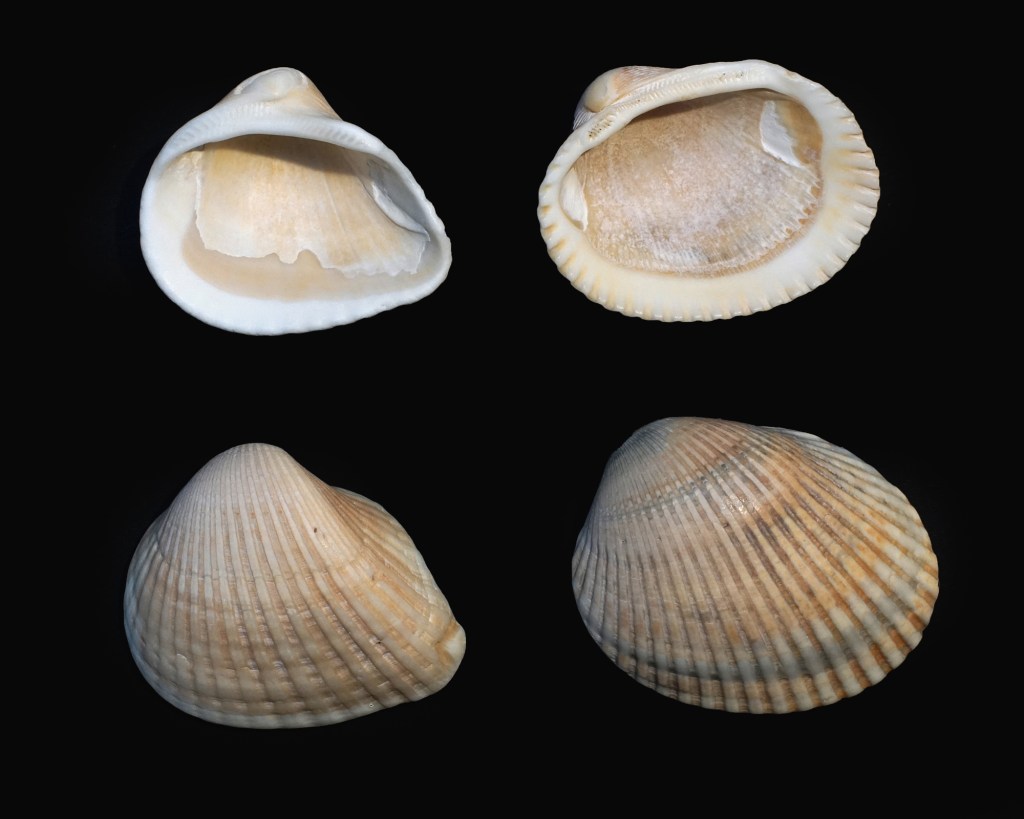

2. Disc Dosinia Clam

The Disc Dosinia clam (Dosinia discus) displays an exterior valve yellowish-white in color with a pure white interior. The valves are moderately thin and quite circular in outline with a small dominant beak. A distinct feature of Disc Dosinia is the fairly even concentric ridges of about 20 to 25 per inch. Another species, Elegant Dosinia, has about 50 ridges to the inch.

- Size: Average 2 inches, up to 3 inches

- Habitat: Just offshore in moderately shallow water and paired valves are often commonly found

- Range: Virginia to Florida, east to the Gulf States and south to the Bahamas

3. Atlantic Surf Clam

The Atlantic Surf Clams (Spisula solidissima), are also known as Hen Clam, Bar Clam, Skimmer Clam, or Sea Clam. They prefer the surf environment on sandy shores feeding on minute plant and animal life that washes back and forth in the waves. After severe storms, beaches are sometimes covered with thousands of these clams! Beachgoers will often pick-up one of their large empty shells to dig with in the sand or take home as a decorative dish. Atlantic Surf Clam valves’ outer surfaces are colored white to yellowish-white, sometimes with added gray. Their interior valves are white with a slight iridescence. The shells are sturdy and triangular-shaped displaying thin concentric growth lines over their exterior shell. They grow fast and large and are prized by humans for their sweet flavor. U.S. wild-caught Atlantic Surf Clam is a smart seafood choice because it is sustainably managed and responsibly harvested under U.S. regulations. They can live up to 35 years.

- Size: Up to 3 inches

- Habitat: Warm coastal water near shore, typically in surf waters

- Range: Predominantly from Nova Scotia, Canada to North Carolina and as far south as Florida to portions of the Gulf States

4. Eastern Oyster

The Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica) can go by several names, including, Wellfleet Oyster, Atlantic Oyster, Virginia Oyster, or American Oyster. Their shell is heavy and possesses a teardrop-oval shape that varies greatly. Sometimes they have scaly concentric layers over their outer surface, and sometimes with irregular concentric rings, and yet sometimes with irregular vertical ribs. It’s interesting to note that they can grow to any shape necessary. The Eastern Oyster shell varies in color from white to gray to tan, or with pinkish markings. The right or top shell is flat with a purple muscle scar on the interior, while the bottom shell is cupped with a dark muscle scar.

Eastern Oysters are very popular commercially. Today, less than 1% of the original oyster population that lived during 17th-century when the origianl colonists arrived is thought to remain in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. The Eastern Oyster is the state shellfish of Connecticut, and its shell is the state shell of Virginia and Mississippi, and the shell in its cabochon form (polished) is the state gem of Louisana.

- Eastern Oyster Quick Facts

- Eastern Oysters exhibit fast growth and reproductive rates.

- They originally mature as males, then later develop female reproductive capabilities.

- An adult oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water in one day.

- Oysters can live out of the water during cooler months for extended periods.

- These oysters often attach to one another, forming dense reefs that provide habitat for many fish and invertebrates.

- They are sought after for their creamy white meat and firm texture with a mild, sweet flavor.

- Size: Average 3–5 inches, Up to 8 inches

- Range: Brackish and saltwater from shallow bays 8 to 35 feet deep, often concentrated in oyster beds or rocks

- Habitat: From Nova Scotia, Canada, south to Florida, east to the Gulf of Mexico and further south as far as Venezuela

5. Spiny Jewel Box Oyster

The Spiny Jewel Box Oyster (Arcinell acornuta) possesses a thick, strongly curved shell with knobs or longer spikes along 7–9 rows of spines. Fresh specimens have extended spikes and resemble the thorny oyster described below. The spikes become worn down by the surf and sand like the pair in my example, or the spikes can break off entirely. They can dipsly a variety of colors including white, yellow, pink, purple, orange and even sometimes green, often with combinations of these shades, making them look like colorful jewels on the beach. Their colors vary by species and can include bright hues like magenta and deeper tones, with some even showing iridescent effects, creating diverse and beautiful shells. This bivalve animal attaches itself to an offshore rock or substrate. This answers the question why beachcombers rarely find these beautiful bivalves in their full glory with both valves attached. Also, because they cement themselves to objects, their shells can be irregular and variable in shape.

- Size: Up to 2 inches

- Habitat: Attached to rock, coral or shells in warm shallow water (sometimes in deep water) and exposed to air during low tide. Later in life, they become detached

- Range: North Carolina to Florida and the Gulf of Mexico

6. Atlantic Thorny Oyster

Atlantic Thorny Oyster (Spondylus americanus) shells normally show the telltale protruding thorns or spines, but after the animal dies and washes-up on the beaches, it typically loses its thorns due to wind and surf, which is likely what happened to my sample shown above. Thorny oysters possess a thick shell with a vibrant spectrum of colors, including bright orange, deep red, rich purple, yellow, pink, cream, and white, often with combinations or banding. They can be circular, oval, or irregular in shape. While they often have a generally round outline, their shape is highly adaptable, allowing them to conform to the crevices or surfaces whereever they attach.

- Size: Up to 5 inches

- Habitat: Deepwater reefs, especially in areas with high sedimentation. It is often lodged in a crevice or concealed under an overhang

- Range: North Carolina and Texas southwards to Venezuela and Brazil

7. Digitate Thorny Oyster

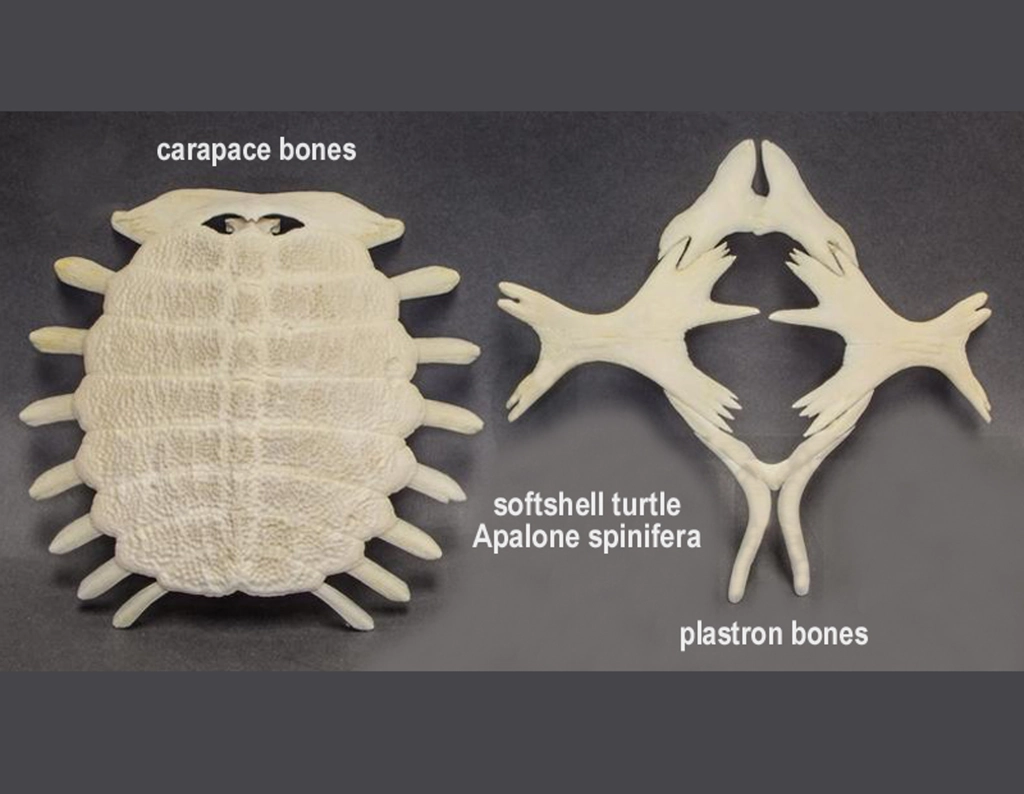

Digitate Thorny Oyster (Spondylu stenuis) is often mistaken for the Atlantic Thorny Oyster (Spondylus americanus). There are many species of Thorny Oysters from the genus “Spondylus” that vary considerably in appearance and range. They are also known as Spiny Oysters. However, they are not true oysters, yet they share some habits such as cementing themselves to rocks or other hard surfaces almost always with their lower valve. They are actually more closely related to scallops. Also, the two halves of their shells are joined with a ball-and-socket hinge rather than with a toothed hinge, which is more common in other bivalves.

The Digitate Thorny Oyster displays a thick lumpy shell most often with thorns, although they have fewer than most spiny oysters and are generally thicker, shorter and flatter rather than pointy. Their spines often break off or are lost after the animal dies, frequently appearing as “naked” or smooth shells on beaches. Some varieties are whitish, pink, reddish or orange. Interior is whitish with a wide darker band around the perimeter. Note: The example above of the Digitate Thorny Oyster has a tubeworm casing attached to it.

….

- Size: Average 3 inches, up to 5 inches

- Habitat: Attach to coral reefs or rocky reefs depending on species in shallows or in deeper waters

- Range: North Carolina around Florida to Texas, southwards to Venezuela and Brazil

8. Jingle Shell Oyster

The Jingle Shell Oyster (Anomia simplex) also known as Mermaid’s Toenail and Saddle Oyster, is a bivalve with thin, translucent, irregular shaped, pearly valves. The exterior valve is curved, usually yellow, silver, whitish or orange, and the interior valve is flat and whitish with a hole at the apex. It has a fleshy appendage (byssus) which passes through the hole to anchor itself upon rocks, seaweeds, or old shells. Consequently, usually only the upper valve washes ashore. Jingle Shells are often attached to submerged objects so thickly that one grows on top of another. Consequently, oyster dredges will bring them up in quantity. People use them for crafting and they make lovely wind chimes that create a sweet sound.

- Size: Up to 2 inches

- Habitat: Shallow waters, beaches, oyster beds, and mollusk shells.

- Range: Nova Scotia, Canada to Florida, Texas and the West Indies

9. Atlantic Kitten Paw Clam

Atlantic Kitten Paws (Plicatula gibbosa) are related to oysters and sometimes are called Cat’s Paw. Still, I prefer the former as they are tiny little seashells no bigger than a penny and too cute to be associated with the mighty hunter. Their valves vary in color and are almost flat, but tough, with a bumpy texture and show an irregular triangular shape resembling their name. They typically attach themselves to rocks using the left valve, so it’s more common for seashell hunters to find the right valve onshore.

- Size: Up to 1 inch

- Habitat: Offshore in sandy substrate up to 300 ft (91m) depth

- Range: From North Carolina to Florida, east to Louisiana and as far south as the West Indies

10. Tampa Tellin Clam

Tampa Tellin (Tampaella tampaensis) clamshells are colored opaque white (sometimes tinged pinkish-orange) with a shiny white interior. They display slightly inflated, oblong-shaped valves with very thin concentric ridges on the exterior. The valve is fairly symmetrical from its somewhat pointed beak. The valves are relatively thin and compressed. The hinge is not strong, and shells washed up on the beach are often broken. In general, Tellin clamshells belong to a family which is often considered the aristocracy of bivalves. Of several hundred species, scores are found along both U.S. coasts, especially in the warmer waters of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Some Tellins are rose-colored and attractive with banded patterns, very desirable to collectors, but most are white to creamy colored.

- Size: Average 1/2 inch up to 4 inches

- Habitat: Shallow sand and grassy inland bays and lagoons

- Range: Florida to Panama and Texas

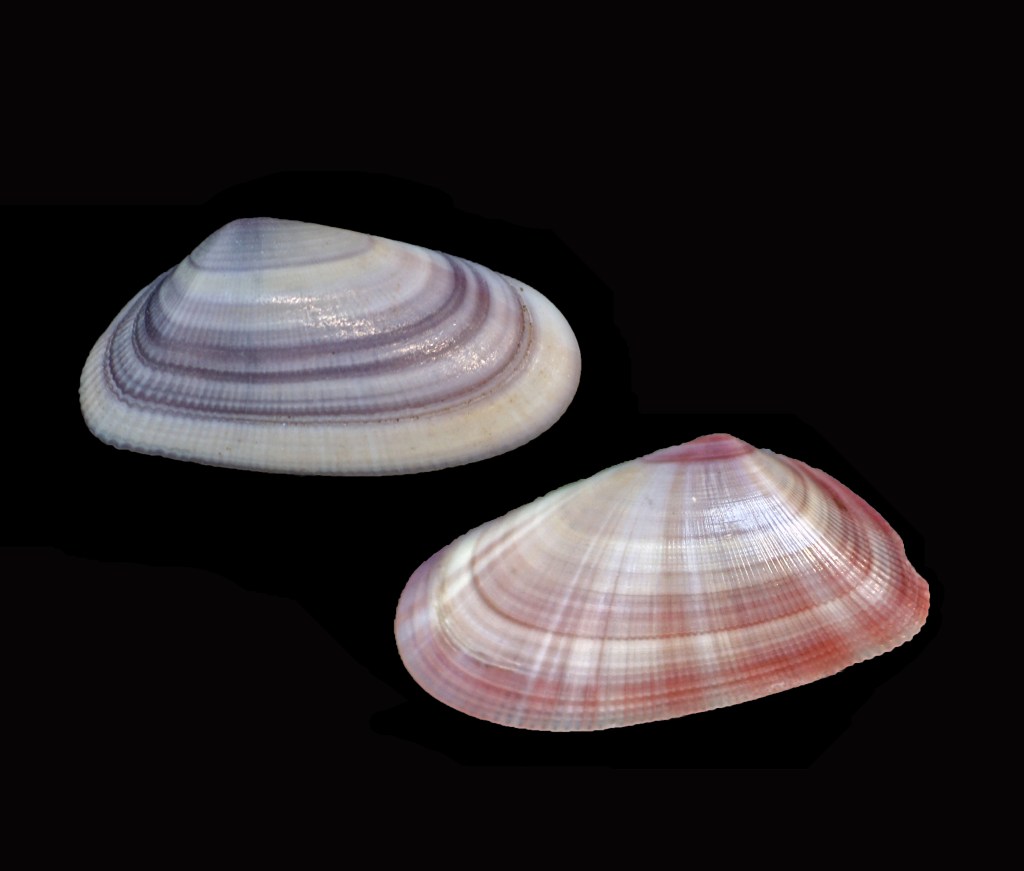

11. Speckled Tellin Clam

Speckled Tellin (Tellina listeri) also known as Interrupted Tellin, has an exterior valve that is shiny, creamy-white with purplish-brown rays or speckling. The interior is white with the colors showing through. The shell is moderately thin, long and oval. The valve has strong concentric lines and a crease extending from the beak to the edge. It is not edible.

- Size: Up to 2 inches

- Habitat: Moderately shallow water, but buries itself deeper in the mud and sand than most bivalves

- Range: North Carolina to Florida and Brazil